“We’re ‘TiVo-ing’ this winter weather so that we can use that for air conditioning come summer.”

–Kent Udell, U of U professor

SALT LAKE CITY – This is the time of year when many start to wish cold winter weather would go away, but some University of Utah scientists are trying to save the winter cold and use it next summer.

This week the students finished installing an experimental system that will store the cold underground in a giant ball of ice.

“I love winter!” said Prof. Kent Udell. “I love the cold. The cold means money in the bank for us, in terms of building the ice balls.”

The project has been in the planning stages for months, but now it’s a reality behind the campus building that houses the Office of Undergraduate Studies.

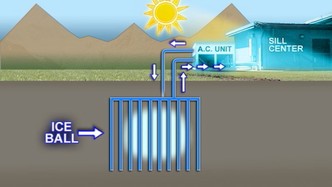

Udell’s team from the Department of Mechanical Engineering created a system of 19 connected vertical pipes that extend 50 feet into the ground. The pipes will circulate a refrigerant similar to Freon from deep underground, to the surface, and back down again.

When exposed to the cold winter air, the refrigerant will become chilled. As it goes back into the ground, it’s expected to freeze moisture in the soil, creating a ball of underground ice 35 feet in diameter.

The payoff comes when winter changes to summer. Freon chilled by the ice ball will be pumped up to the building’s air-conditioning system to cool the building as the ice ball melts. Udell compared it to recording a TV show for use at another time.

“We’re ‘TiVo-ing’ this winter weather so that we can use that for air conditioning come summer,” Udell said.

In theory, a similar system could store summer heat underground and use it to warm up the building in winter.

“You won’t need any electricity at all,” said Ph.D. candidate Bidzina Kekelia. “If you put small solar panels and power the small pumps — liquid pumps that we are putting in — you won’t be using any power from (the) grid.”

Udell expects the installation on campus will ultimately cost just over $20,000. He believes such a system could pay for itself within two years in reduced energy bills if it’s used on a building with a high demand for cooling, such as a computer data center. With an office building like the Office of Undergraduate Studies, he guesses it might take 10 years to pay for itself.

“This is the first time this has ever been done on this scale” Udell said. “So the cost numbers are one of the things that are going to be worked out as we find out how well this works.”

Kekelia said if such a system became widely used it could reduce the need for electrical power plants.

“Which is lots of savings in power,” Kekelia said. “Besides, its free. I mean, you’re getting free cooling, free air conditioning or, in future, free heating.”

“This should last for many decades,” Udell said, “and will continue to pay dividends and give us free heating or air conditioning as the technology develops, every year from here on out.”

The installation is now complete, except for the connection to the building’s air conditioning system. Udell hopes to have the system operational in about a month, so they can start saving winter cold before it goes away.